Happy Wednesday, FOC summer reading clubbers, and forgive my tardiness in posting this week. I haven’t relished the thought of having the “n-word” prominently displayed on my blog for all search engines to find. But it probably is time we addressed the question of race in O’Connor’s fiction.

By way of entry into the question of race, I will tell you a story about the editorial process for my forthcoming O’Connor biography, The Terrible Speed of Mercy (which, I recently learned, has a new publication date of August 22, six weeks from today). The book had gone through a few rounds of edits when somebody at Thomas Nelson said, “Wait just a minute…we don’t use the ‘n-word’ in books published by Thomas Nelson.” A perfectly legitimate concern.

Indeed, the n-word appears thirteen times in my manuscript, and twice before you even make it out of the introduction. One solution would have been to “bleep out” the word, substituting “n—–” for the offending word. But eight of those thirteen instances appear in the title “The Artificial N—–.” Which is a problem insofar as you can’t very well bleep out part of a story title. Somebody raised the possibility of keeping the title intact, bleeping out the other five instances of the n-word, and writing a Publisher’s Note explaining that, as far as that particular word goes, things were different in O’Connor’s time. I didn’t much like that solution, largely on the grounds that the word–especially among O’Connor’s readership–was as offensive then as it is now.

Lest you think this is a story of a publisher being overly cautious and politically correct, let me say that Thomas Nelson was correct to think long and hard before putting out a book that includes thirteen instances of a word as inflammatory as that. In the end the publishing team decided to leave the manuscript as it was in and include the following note at the beginning:

A Note About Diction

A highly offensive racial slur occurs some thirteen times throughout this book, in each case quoted from Flannery O’Connor’s fiction or correspondence. The publishing team discussed at some length how best to handle this word in light of the sensibilities of twenty-first century readers. In the end, we decided to let the word stand in its full offensiveness, on the grounds that the repugnance the reader feels at the word is a key reason O’Connor used it in the first place. It may be true that there was more open racism in the 1950s and 1960s than in the twenty-first century, but that hardly explains why O’Connor used the “n-word” in the thirteen instances quoted in this book. A reader of literary fiction in the 1950s would be no less offended by the word than a reader of literary fiction in 2012. To expurgate O’Connor’s language would be to suggest that we understand its offensiveness better than she does, or perhaps to suggest that the readers of this book are more easily offended than O’Connor’s original audience. We have no reason to believe that either is true. So we leave O’Connor’s language intact, and we leave you with this warning: you may find some of the language in this book offensive; that is as it should be.

This article by Rachel D. Held gives a sense of how much courage it has taken on the publisher’s part to let such offensive language stand.

So then, race in “The Artificial N—–.” It is common in O’Connor’s fiction to see white characters express racist attitudes. I can’t think of a single instance of O’Connor endorsing those attitudes in any of her stories or novels. From a race perspective, the troubling thing about “The Artificial N—–” isn’t that a couple of hillbillies turn out to be racist. More troublesome is the fact that this is one of the few O’Connor stories in which a character clearly sees the error in his ways and appears to receive the offer of grace. And yet Mr. Head’s racism doesn’t get fixed.

Consider this remarkable moment at the end of the story, when Mr. Head realizes what an awful thing he has done in denying his grandson:

He stood appalled, judging himself with the thoroughness of God, while the action of mercy covered his pride like a flame and consumed it. He had never thought himself a great sinner before but he saw now that his true depravity had been hidden from him lest it cause him despair. He realized that he was forgiven for sins from the beginning of time. . . . He saw that no sin was too monstrous to claim as his own, and since God loved in proportion as He forgave, he felt ready at that instant to enter Paradise.

This moment of self-awareness immediately follows a moment of reconciliation between Nelson and Mr. Head. And that moment of reconciliation is signaled by their sharing of a joke–an unmistakably racist joke!

What I’m suggesting is that if you or I were were writing a story about a racist coming face-to-face with his own sin, you or I would probably show him becoming less of a racist. Not Flannery O’Connor.

What do you make of that?

Bonus reading recommendation: The best discussion of O’Connor and race and sin and redemption can be found in Ralph C. Wood’s book, Flannery O’Connor and the Christ-Haunted South, Chapter 3.

Chris

Interestingly, this aspect of the story was not the one I was thinking about the most, although it did revolve around the artificial nigger itself, and how that played into the redemption. In looking at that scene at second time, I did notice that the statue is said to be the same size as Nelson. I wonder if that is of any significance. This story is quite puzzling, and apparently it was for O’Connor herself. It was her favorite story, by her own admission, but also one of the most difficult for her to write. I’m still not sure what to make of it.

I will say the opening descriptions of the moon were wonderful to read.

Bryana Johnson

In addition to the comments I made in a longer comment earlier, I agree with Chris about this: I didn’t feel like the racism in the story was the main point. It was there, and O’Connor utilized it, but it wasn’t the central message. I think it’s important to understand Mr. Head’s times and his culture, also. For many elderly people living in certain pockets in the south at that time, racism wasn’t a conscious decision they made somewhere along the way. It was what they grew up with from the time they were young children. Some of them (like Mr. Head, it seems) also didn’t spend much time with African-Americans at all. They had no chance to change their minds. The shocking thing for these folks would be if they were not racist. It is not at all shocking that they were.

This doesn’t, of course, undermine the steep gravity of the sin, but it does, I think, serve to demonstrate that some sudden transformation to non-racism is not an essential for Mr. Head to have truly found grace in some measure.

Philip Wade

Perhaps I have a incorrect take on this one. I thought Mr. Head and Nelson reverted to their racism after the trauma and epiphany, because it was their comfort zone. It was their common ground. Mr. Head (what a strange name) felt the need to say something wise to reestablish his role in their relationship, “and heard himself say” something familiar.

What you quote above comes after that, and you skipped part of it. Mr. Head understood that mercy was given to all men and was the only thing they would carry back in death to their Maker, and he was ashamed that he had so little of it. Maybe that’s his understanding that his hatred and fear of black people is sinful.

But when I read this, I wondered at the Edenic imagery at the end. When they return to their home junction, the trees are a like a fence around the garden, the silver moon is back, and the train leaves like a serpent. Even though Mr. Head has had an astonishing revelation by way of his own sin, have they returned, not to a place of truth and wisdom, but merely their own racist comfort zone? The snake that took them into the city lied to them for a full day, but thank goodness that’s behind them now. Maybe that part is a misread. I’m willing to believe Mr. Head has recognized something of the sin of his fear and hatred. He has returned to Eden and redemption, and the snake is leaving the garden, but racism is still his habit and so, it’s still comfortable. It will take time for him to let it go.

Nelson, on the other hand, just got scared.

Jonathan Rogers

Philip, could you clarify what you’re saying about the garden imagery there at the end? Are you suggesting that O’Connor uses this language ironically? That Mr. Head hasn’t actually received this mercy? I tend to see this as another moment in which the mundane and the transcendent coexist, and Mr. Head is willing to see it for the first time, now that he knows he needs mercy.

After thinking about your comment, Philip, I’m open to the possibility that I’ve been reading this ending wrong. I wasn’t really paying attention to the language right before Mr. Head’s lame joke. Mr. Head still feels the need to prove himself when he makes that joke. Maybe he’s not opening himself up to grace yet; it seems that it’s there on his home ground that he fully awakens to the mercy he needs so badly.

Philip Wade

I meant to say that I originally read the story with ironic garden language at the end, because everything up to that point had been seen through Mr. Head’s twisted POV (and a little of Nelson’s). But you have helped me see the redemption, so I agree with you that Mr. Head has received mercy and dwells on it again at the end, like you say.

To answer your question about the racism that doesn’t seem to dissipate at the end, I suggest Mr. Head may or may not see the sin there–his lack of mercy for all men–but it’s still where he is most comfortable. It’s in his nature, his culture. So when he says they don’t have enough niggers in Atlanta that they need artificial ones, he is just stepping back into his comfort zone–even if he is starting to understand how wrong it is. It will be a long haul for him, I think. It’s the words, “and heard himself say,” that make me suspect Mr. Head does start to see the sin in his racism, but he won’t be able to just drop it. He’s thought that way his entire life.

Sarah J

And isn’t that the way with all of us? Even after we recognize something wretched in ourselves and determine to change, we at times “find ourselves” back in those same twisted habits. Prone to wander, but not outside of God’s grace…

Dananddawn

I took the joke more as if it was ironic. The idea that in the white suburbs they did not have enough negos. That it was a shame in a way that the white section would only allow artificial negors and not real one.

Matt Owen

I think I read it in a similar way to Philip. Both Nelson and Mr. Head spend the story trying to best the other starting with something as simple as getting up first. Each one is proud and each one thinks he knows more than the other. Each one thinks he is superior. This jockeying for position finally spirals out of control and splits them apart. It appears to me that the moment of “grace” Mr. Head receives is not necessarily a personal humbling that leads to reconciliation. Instead they unite based on a shared perception that they are superior to another group of people. I found Mr. Head’s relief that the relationship had been mended to be hollow since the occasioning incident of the healing essentially left them as they were in their pride.

Philip Wade

I found the word “nigger” did not bother me in this story as much as it did in other stories where there’s no contrast between the characters and the narrator. In this story, Mr. Head calls someone a nigger, but the narrator describes him as a Negro. (The sultry women isn’t described as a Negro, is she? Isn’t she described by her skin color and dress?)

I’ve been waiting for this story to share another one about this word. A Christian fiction author wrote a suspense novel steeped in the deep South, and the author said he and his publisher wrestled with this one word that was very offensive, but they felt it was culturally relevant to the story. I had read the story, and when I read these comments on the author’s blog, I couldn’t think of what word he was referring to. Nothing had stood out to me. Of course, it was the N-word, a word I dislike and don’t use but don’t blink at when I see it in historic context. Maybe I’m too steeped in the deep South myself.

C. N. Nevets

There is only a disconnect if one assumes that the reception of mercy and grace immediately not only imputes sanctification but also transforms the individual from a fallen man to the likeness of Christ. If one allows that the recognition of one’s sinful nature, one’s need for mercy, and indeed the availability by grace of that mercy need not instantly chance both the essential and the phenomenal man, than I don’t see anything surprising or confusing about this.

That said, I don’t think it’s a full slide-back either… He looked at Nelson and understood that he must say something to the child to show that he was still wise and in the look the boy returned he saw a hungry need for chat assurance. Nelson’s eyes seemed to implore him to explain once and for all the mystery of existence.

Mr. Head opened his lips to make a lofty statement and heard himself say, “They ain’t got enough real ones here. They got to have an artificial one.”The spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak.The way I read this story, the sin which he recognized in himself was a dual treachery toward Nelson. Most immediately, he had denied Nelson in his time of time. More fundamentally, I think he saw his own corrupting influence. He had created in the boy an “artificial nigger,” of his own — someone who was black of skin (“not tan”) and to be hated, feared, and looked down on. There aren’t enough devils in the world. He had to give Nelson an artificial one.The way I see it, it’s a truth told timidly, a confession made in the weak, corrupt language of his own sinful nature. He offers it to Nelson as a sign of wisdom, to give him reassurance. But he’s hearing it himself.

Philip Wade

“There aren’t enough devils in the world. He had to give Nelson an artificial one.” That’s excellent. It seems Mr. Head regrets it too, ashamed he has so little mercy.

Jonathan Rogers

C.N., I certainly agree with you that one wouldn’t expect an instant transformation of a man like Mr. Head in real life. But for an author whose purposes are spiritual, that kind of verisimilitude is a risk. O’Connor, as always, risks being misunderstood rather than oversimplify or otherwise contort reality to make a “spiritual” point.

My point, really, is that it’s noteworthy that O’Connor, even as she enacts Mr. Head’s moment of grace, makes a point of demonstrating that he’s still a racist. As you say, his spirit is willing for the first time, but his flesh is still weak.

Your last paragraph, by the way, is especially fantastic.

Amy L

I feel that they haven’t really received grace. Mr. Head never apologizes to Nelson. They do not repair their rift by facing their sin. They repair their rift by sharing in pride. Mr. Head never acknowledges that the print-out fortune he got was as inaccurate as his weight. No, instead he pretends that he is all of those things, that he hasn’t sinned, by getting Nelson to join him in his racism.

Nelson was not a racist before this day. Even Mr. Head knows this, as he points out that when Nelson was a baby, he wouldn’t have recognized anyone’s race. He had been taught to hate “niggers,” but he thought that “black” meant actually black, not a shade of brown. When the dark-skinned woman gives him directions, he wants to love her. (Again, the very inaccurate fortune plays a role in his choosing to follow his grandfather’s racism. That was an easy one – if the numbers are so wrong, then the words are probably wrong, too!) He ends as a racist because it’s the only way to reconcile with his grandfather.

If Mr. Head’s realization of God’s mercy was full, I think he would have actually confessed aloud the one sin that he did realize he had committed – publicly disowning his grandson in the face of danger. That would have allowed them to reconcile for real. When Nelson accepts the racism instead of waiting for a real apology, Mr. Head has his moment where he feels he has received mercy. He comes away thinking that he has shown humility, but he hasn’t. Racism is the perfect example of foolish pride.

I think I’m using too many words to say what I mean.

I don’t think mercy can be complete without confession, especially not within a Catholic worldview.

I don’t think they do receive grace in that moment. Their lives are not changed at all – quite literally, they go back to their home, and Nelson says he never wants to return to the city that could have changed his life. I think that Mr. Head is relieved that he doesn’t actually have to face his sin.

His epiphany contains two phrases that make me think he really hasn’t lost any of his pride: “his true depravity had been hidden from him lest it cause him despair.” He feels that God had been taking special care to make sure that he never felt despair at his own sinfulness. I find that prideful, and I think that a Catholic would, too. (maybe I’m wrong there). We ought to know our own depravity. “He saw that no sin was too monstrous to claim as his own, and since God loved in proportion as He forgave, he felt ready at that instant to enter Paradise.” This strikes me as pompous. He is willing to claim any monstrous sin, so that he can feel an equal proportion of God’s love, enough to send him straight to Paradise. He isn’t confessing any particular sin – he is “claiming” it so that he can have a greater share of heaven. That didn’t strike me as humble.

yankeegospelgirl

I saw an interview with British actor Martin Freeman (very eccentric and interesting fellow), where he discussed his love for old-fashioned Motown/R & B but said he found rap distasteful. He said one of the reasons is that he doesn’t like the way the word “nigger” gets thrown around constantly in rap lyrics. “Nigger this, nigger that…” What’s ironic is that I later found an article criticizing Freeman for this. I kid you not, this woman was saying, “White people have no right to use the term, but black people have the right to use it whenever they feel like it.” So apparently it was this big faux pas for Freeman to dare to say that he found this word offensive in black rap music, because foul racist talk is culturally okay as long as it’s all within the same race.

Alex Vercio

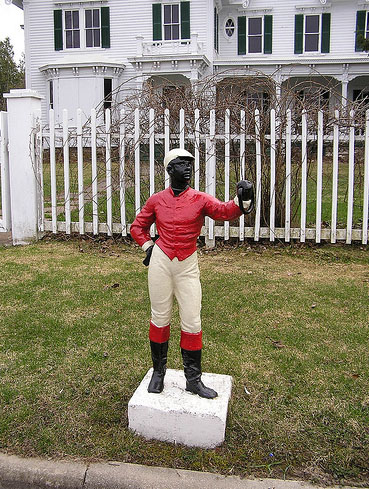

The point of grace in this story reminded me of something that came up in the last story, A Temple of the Holy Ghost. The way that the girl in that story comes to understand grace is through an act at a carnival that gets shuts down because of its immorality. Here the moment of grace is brought about through the communion of racism. Maybe Flannery O’Connor was going another step by saying we could be brought to grace by something as ugly, and ungraceful as racism. That moment of mercy, though, is fascinating to me and I don’t get exactly what’s happening. Those lines are packed but I still don’t understand the moment. “They stood there gazing at the artificial Negro as if they were faced with some great mystery, some monument to another’s victory that brought them together in their common defeat.” What’s the great mystery of the figure and how does it signify another’s victory and their common defeat? Is there something more than racism going on here?

Jonathan Rogers

Alex, I don’t know if this helps or not, but in one letter FO wrote, “What I had in mind to suggest with the artificial nigger was the redemptive quality of the Negro’s suffering for us all.” Truth to tell, I don’t quite understand what that means, nor do I fully understand the lines you referred to. I can get from “Mr. Head needs redemption” to “Mr. Head has received mercy” and it seems that O’Connor meant for Mr. Head and Nelson’s encounter with the lawn statue to bridge that gap, but I don’t understand exactly how that happens.

Amy L

Bugger. That really makes sense to me, actually (contrary to what I had posted earlier). And it hurts, too. Mr. Head and Nelson can receive mercy because of the sacrifice made by black people – because they are treated the way they are treated by white people. A little like how the DP was sacrificed for the balance of the farm.

Bryana Johnson

I’ve been enjoying reading through all of the comments on this story, but am still more than a little undecided as to what to make of it. Somehow I just don’t feel like O’Connor gave us enough clues to enable us to solve the puzzle. As with others of her stories, (i.e. The River), so much really depends on how perfect grace has to be in order for it to be genuine in her eyes. And I don’t know the answer to that question. I’m sure that you, Jonathan, having a much broader knowledge of O’Connor’s work and life, have some kind of take on this. My question for you would be do you get the sense that imperfect salvation in her writing is meant to point out hypocrisy, or that she really sympathizes with it?

I live in the south, and run into the Christ-hauntedness of it on a regular basis. I tend to become very impatient with the partially good things and the half-right faith and the prevailing half-wrongs that mar so much of what professes to be lovely. So I definitely understand this perspective. I get the impression, however, when reading O’Connor’s stories, that she feels a deep sympathy for the characters whose utter inadequacies she displays in ruthless detail. For instance, while we find Mr. Head’s arrogant and selfish self despicable, we want things to go well for him because he is so pitiful. Time and again it is this pitifulness, this childishness, this overwhelming brokendownness of humanity that I take away from her stories. And I don’t know if that is something that stems from my own character and my own personality, or if it really is the central theme of her writing.

What do the rest of you think about this?

Jonathan Rogers

Bryana, I love this question. For my part, I don’t think that the point is that Mr. Head is a hypocrite, but that the healing of his brokenness is only now beginning. I agree with you that O’Connor felt a lot of sympathy for any character who understands his own brokenness. But she could be really hard on those who refuse to see their need of mercy.

Madeleine's husband

From Madeleine and her husband, we both think that the grace and point of the story is laid out in clear and undeniable terms at the end. It’s a beautiful picture of the gospel. God forgives the sins that we commit and the sins that are ingrained in the depravity of our soul (original sin). For Mr. Head, he had to have an outrageous act show him just how proud he has always been, but “the action of mercy covered his pride like a flame and consumed it.” We don’t particularly think that racism is the point. The question we have (be interested in Jonathan’s opinion) is why she is so blunt in explaining the gospel application here, when in another stories, the moral is so subtle (such as “A Good Man is Hard to Find” – I thought the grace in the story was as hard to find as the good man).

Jonathan Rogers

Madeleine (and husband), I don’t know why FO was so explicit in her portrayal of the action of grace here. She’s similarly explicit in “Revelation,” which we’ll get to in August, but these are really the only two of her short stories where she is.

I should point out, by the way, that I agree with all of you who say that racism isn’t he main point of this story. It just happened to be what was on my mind when I sat down to write about the story.

Jeff Brown

In one of her letters, O’Connor wrote, concerning this story, “I wrote that story a good many times, having a lot of trouble with the end. I frequently send my stories to Mrs. [Caroline] Tate and she is always telling me that the endings are too flat and that at the end I must gain some altitude and get a larger view. Well the end of The Artificial Nigger was a very definite attempt to do that and in those last two paragraphs I have practically gone from the Garden of Eden to the Gates of Paradise. I am not sure it is successful but I mean to keep trying with other things.”

So apparently the explicitness was part of her attempt to gain “altitude.” It’s interesting that she did this in response to someone else’s suggestion, that it wasn’t her idea to try this new way.

Micah Hawkinson

I think the racist framework lends a lot to the story, both in characterization and in creating conflict between Nelson and Mr. Head. I also think that the framework’s power is simply too great to be overcome by Mr. Head’s moment of grace. Maybe we would believe such a strong shift over the course of a novel, but I think it would be too much to take in a story of this length.

One thing I love about this story is how it suggests that the very concept of “Nigger” is itself artificial. Since it does not fundamentally exist, it must be socially constructed and transmitted.

When Nelson and Mr. Head are arguing at the beginning of the story, Nelson asks, “How you know I never saw a nigger when I lived there before? … I probably saw a lot of niggers.”

Mr. Head’s frustrated response is a great example of irony: “If you seen one you didn’t know what he was,” Mr. Head said, completely exasperated. “A six-month-old child don’t know a nigger from anybody else.”

This point is underscored again when they see the large coffee-colored man on the train: Mr. Head’s grip on Nelson’s arm loosened. “What was that?” he asked.

“A man,” the boy said and gave him an indignant look as if he were tired of having his intelligence insulted.

“What kind of a man?” Mr. Head persisted, his voice expressionless.

“A fat man,” Nelson said. He was beginning to feel that he had better be cautious.

“You don’t know what kind ?” Mr. Head said in a final tone.

“An old man,” the boy said and had a sudden foreboding that he was not going to enjoy the day.

“That was a nigger,” Mr. Head said and sat back.

Nelson jumped up on the seat and stood looking backward to the end of the car but the Negro had gone.

This transmission of social boundaries is a vital part of the relationship between generations. The older generation’s knowledge of such mysteries gives it definite authority and some measure of power over the younger generation. One reason that this story is so powerful for me is that it emphasizes how very tenuous that authority is.

In the moment when the old man and the boy stand together, dumbfounded by the artificial nigger, their shared human helplessness becomes clear. They are united not in triumph or strength, but in their common weakness. The boy needs some sort of explanation so he can make sense of the situation, the old man provides it because it his duty to convey wisdom (not necessarily because he actually has any wisdom), and the balance of their relationship is restored.

In the end, I think the grace poured out on Mr. Head has the effect that grace always has: it restores, heals, and — in at least some small way — helps things to get closer to how they were always meant to be. That doesn’t mean we become instantly perfect, but perhaps we get a little bit perfect-er.

Madeleine

Well said, Micah. Your last few paragraphs helped me put into words what I was thinking. I was so taken with the paragraphs in the beginning about Mr. Head being like a guide. As you stated, Mr. Head sees himself forming the younger generation. He has a moral mission planned. The statement from the fourth paragraph sets the stage for me,“Mr. Head lay back down, feeling entirely confident that he could carry out the moral mission of the coming day.”

This is a story about pride and being taken down a notch. It’s Mr. Head’s plan for Nelson, but it ends up the order of the day for himself. His pride took several hits during the day and his was in agony thinking all was lost with Nelson. Then he had a chance to redeem himself, to say something wise. Instead he heard himself saying something foolish. Yet miraculously the kid took it. The balance was restored, as you aptly said, Micah.

When they get home Mr. Head reflected on all this and realized how foolish and ineffective he truly had been not just all day, but all his life. “While the action of mercy covered his pride like a flame and consumed it.” It was in his weakness that his moral mission was accomplished, through mercy he didn’t deserve.

Loren Warnemuende

This is so good, and so clear, Micah. I felt similarly about how Mr. Head had to “instruct” Nelson as to what a nigger was, and how Nelson then looked at the black man with hatred: “He felt that the Negro had deliberately walked down the aisle in order to make a fool of him and he hated him with a fierce raw fresh hate; and also, he understood now why his grandfather disliked them.” It made me think of the song “You’ve Got to Be Taught,” in the musical South Pacific.

Loren Warnemuende

I read through this and the first comments last week, and didn’t feel up to the discussion. It’s been great to read through everyone’s points now–so many great insights!

Jonathan, I appreciated this story. Didn’t understand it all, but I did like it. I also apologize for saying in the past that I’m always wondering who O’Connor will kill off next. We’ve now had two stories in a row without a death, and I know that’s true in Good Country People, too 🙂 . I am anticipating more stories like these.

I don’t have much to add to this discussion other than my uncomfortable feeling that I have been more like Mr. Head at times than I’d like to admit. How often have I betrayed someone’s trust because I was afraid of looking stupid? Are there times I’ve spoken to my kids in such a way to make myself look wiser and better (and help them realize their inferiority), rather than resting in Christ’s love for me and letting that love and humility flow through me? It’s pretty humbling. I’m thankful for Mr. Head’s breakthrough at the end of the story where he senses God’s amazing mercy.

Madeleine

Hi Loren, I tried to “Like” your comment, but I can’t tell if it shows you that I’m the one who did it. (maybe I’m just “guest”? I’m really bad with this stuff!) Anyway, I always appreciate what you have to say. Thanks.

Loren Warnemuende

Thanks so much, Madeleine! I’ve “liked” a number of your comments, too, and probably have had the same issue. Every time I read one of your comments I think, “Wow! That’s what I was thinking,” or “I hadn’t thought of it that way, and it makes so much sense!” Apparently we are kindred spirits across the ether of the internet 🙂 .