I’m terribly sorry about my absence right in the middle of the Summer Reading Club. I hope to circle back around to the stories we missed–“Greenleaf,” “A View of the Woods,” and “The Enduring Chill.” Meanwhile, I figured it was best just to pick up with the story that was scheduled for this week.

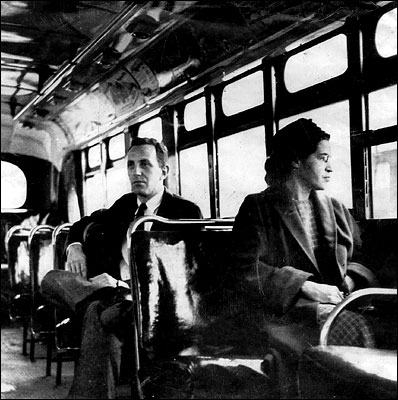

Flannery O’Connor referred to “Everything that Rises Must Converge” as “my reflection on the race situation.” Indeed, though race figures into most of her stories one way or another, “Everything That Rises” is the only story that so consciously and directly addresses the changing dynamics of race in the South as a “situation.” The story mostly takes place on a city bus, that crucible of racial politics in the American South of the 1950s and ’60s.

Julian and his mother form a dyad that we have seen already in “Good Country People” and that also appears in “The Enduring Chill”–the the overbearing mother and the over-educated, progressive, and naive adult child. Then there is the mother’s black doppelgänger. She personifies the convergence that will inevitably result from the rising fortunes of African Americans. The white characters—the liberal no less than the reactionary—find that they are ill-prepared for such a convergence.

One of the most remarkable things about this story, I think, is the fact that in the end it turns out not to be a reflection on “the race situation” after all. O’Connor could have hardly chosen a setting that was more politically/racially charged. She wrote the story in the spring of 1961. Just five years earlier, Rosa Parks’s act of civil disobedience launched the Montgomery bus boycott. That spring–1961–saw the Freedom Riders traveling the South in buses. And yet, on Flannery O’Connor’s bus, the most important dynamics at play are family dynamics, not racial dynamics. The more I reflect on this story, the more I realize how little it has to say about “the race situation” in the segregated South. O’Connor never adjudicates between Julian’s views and those of his mother. Both of them are wrong about the black woman and her son, and for the same reasons: neither sees black their black neighbors as fully human. Julian rejects his mother’s supremacist views, but for his purposes, the black mother and son are useful symbols, not actual people. The white mother’s patronizing of the little boy is matched by Julian’s patronizing of the black mother.

Julian’s great revelation at the end of the story has little or nothing to do with race. The black woman and son are gone, and he is left alone with his dying mother. When he enters into “the world of guilt and sorrow,” his guilt is over his sins against his mother, not over his or his society’s sins against the black woman on the bus or black people generally. Perhaps O’Connor’s “reflection on the race situation” is that even as the races rise and converge, we are still accountable to one another as individuals, not as races. As deep as the “race problem” goes, it is still not our deepest problem; it is one of the most obvious symptoms of our deeper problem of sin.

Bryana Johnson

Yay! So glad that you’re back….I was beginning to think we’d lost you. I mean, for the summer 🙂

I went ahead and finished the book a little ahead of schedule, and wrote a post an article on it over at my website ( http://www.bryanajohnson.wordpress.com/2012/08/13/the-lame-shall-enter-first/ ), capitalizing on my very favorite story: The Lame Shall Enter First. Let’s be honest, it’s probably the easiest of her stories to understand 🙂

Loren Warnemuende

Just popped in to check and was so glad to see this. I was a little afraid something was wrong with my Internet and there was a whole discussion going on out there that I was missing. But then, considering how crazy my summer has gotten in the past few weeks, I figured you were probably in that boat as well.

Now off to read the story!

Anonymous

Do you think that the black businessman also acted as doppelgänger to Julian? Thinking his mother was too naive to see the black woman with the identical hat, etc. Julian doesn’t realize that the black man is treating him in similar fashion to how he viewed/treated others. Also, Julian seemed willing to only associate with a certain class of black people, reflective of his higher education, but also of his own form of prejudice.

I thought Julian’s cries going from “Mother!” (formal and distant) to “Mamma, Mamma!” (his mother’s “real” name) was an especially gripping sequence.

Thanks for the summary.