I’m at the beach this week, so I’ll keep this short and rely on you, dear reader, to do the heavy lifting–which you often do anyway.

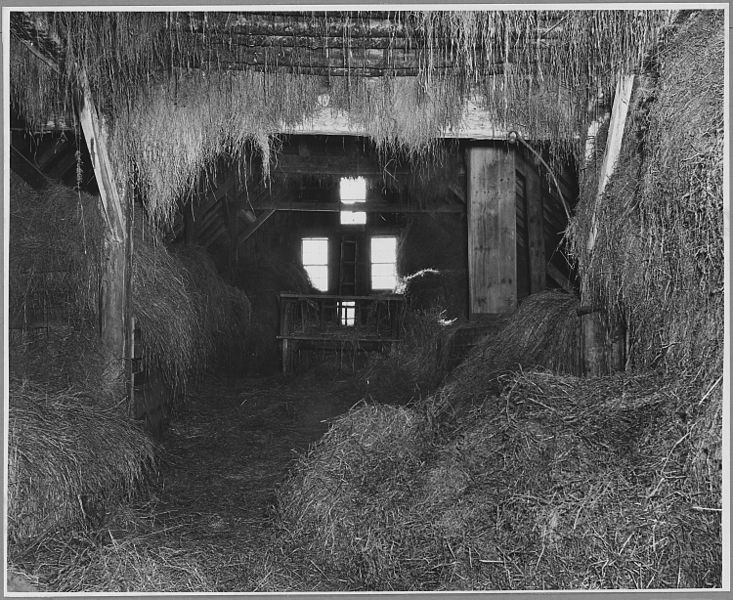

The irony in “Good Country People” is thick and layered. The joke is on Joy-Hulga, and it is an especially mean joke–or, in any case, it appears to be. But the episode in the hayloft, ironically, is also an offer of grace. Hulga has poured her whole self into that wooden leg (I’ll let you work out all the symbolism contained therein). It’s what she has instead of a soul (“She took care of it as someone else would his soul, in private and almost with her own eyes turned away.”) For this devilish figure, the Bible salesman, to take her wooden leg is the cruelest thing he could do. It is as if he is stealing her soul. Except that being stripped of that ugly idol of self is exactly what Joy-Hulga needs from a spiritual standpoint.

I don’t know that there is any evidence in the story that Joy-Hulga receives grace. But the shock of self-realization, as painful as it is, is at least a step in that direction. A few weeks ago we discussed O’Connor’s idea that the devil is always achieving ends that are not his own. Do you see that dynamic at work in this story?

April Pickle

Another deeply thought-provoking and blessedly offensive story! I am eating this up! Room is being made for grace in Joy-Hulga here, however painful. When she decides to let him see the wooden leg, she is finding out that she is willing to let go and trust what she has decided is innocent and really knows her. She is wrong about the salesman (even with her age and all of her education, she is deceived), but in surrendering her rights to the leg, “It was like losing her own life and finding it again, miraculously, in his.” And if she is beginning to idolize him… well, that isn’t lasting long!

Madeleine

I found this story less emotionally affecting than some of the others. I think that Joy/Hulga was portrayed less sympathetically. I didn’t feel as bad about what happened to her because she was a disagreeable person, more so by her own efforts.

But I am wondering if my decreased reaction was because I didn’t personally identify with her much either.

Did anyone else feel less affected by this story? Why or why not?

(This is not to say I didn’t enjoy the story as much. I found it very entertaining and thought the ending was great- I wasn’t expecting that. But I didn’t find myself fretting over poor Hulga or begging my husband to read it so we could discuss.)

April Pickle

I think I had a similar experience with Joy-Hulga. But the fact that I did feel less affected bothered me. So I’ve been thinking about Joy-Hulga, and this idea of idols. At first, we are led to believe that Joy-Hulga’s problem is her lack of a leg. But later we learn that she is able to get around as quickly as the salesman. Yet, she is still such a bitter person. Her problem is much deeper than her physical “impairment.” Perhaps her wooden leg is representative of her attempts to fill that void herself. But it’s wooden, it’s dead and it’s vulnerable to being taken away.

And since you brought up Mrs. Hopewell, I’m wondering if Joy-Hulga’s bitterness is due to the fact that she hasn’t been loved. She is willing to give herself to another (the salesman) when she believes that he truly loves her. She’s wrong about him, but he has brought something out in her that her mother has not been able to do. I’m confident that Joy-Hulga would be angry about the wooden leg being taken, but I think by that time she hops home from the loft, she will be less bitter and more open to grace. Glad FO leaves this to our imagination. It gives me a longing and a hope to see Joy-Hulga opened up and filled to overflowing with the grace she desperately needs.

Amy L

Me too. Even remembering the first time I read some of these stories in high school or college — “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” made my stomach turn, but I then found the ending of this story a little funny.

Madeleine

Also wanted to say I was struck by this sentence, ” Mrs. Hopewell had no bad qualities of her own but she was able to use other people’s in such a constructive way that she never felt the lack.” When I first read it I thought it was saying she never felt lack because she was able to use other people’s bad qualities to her advantage. That could be a great skill to have.

But now that I type it out I see it says she never felt THE lack. Perhaps she never felt the lack of having bad qualities of her own because she was able to use those of the people around her. Ha! I find that a humerous characterization. Either way, I think that sentence was a good one.

April Pickle

I love that sentence, too! Laughed out loud at it and read it aloud to my daughter. What a character! I think Mrs. Hopewell is the antithesis of hoping well, because she lives in a state of denial and insecurity. I can relate to her. Ouch.

Dan

I liked how Flannery gets you to route for the Bible Salesman. How they have no interest in what they believe he is selling. He ends up being just like them, collecting fake things (i.e. artificial leg).

I really thought he was taking the leg so he would force her into buying his Bibles and that he had it planned from the start to take her crutch from her so he could use it as leverage to get her to buy some Bibles.

I agree that there seems to be some devine providence where her crutch is being taken away so she can perhaps find real truth. It goes to the idea that God is always using the devils schemes towards good and not evil.

Flannery seems to like to leave things opened ended and to force her reader to think and perhaps write their own ending to the story. Much like the Prodigal son story where you don’t know how it ultimately will end.

Anonymous

Like others, I particularly enjoyed the humor and irony of the story. Not that O’Connor’s other works aren’t witty, but this one seemed to be especially so. I thought she was particularly clever to parallel Joy-Hulga’s leg and her (assumed) virginity. As the reader, it puts you off-balance a bit when the boy is more interested in her artificial leg than anything else (which is humorous in it’s own right, I suppose). Also, the fact that Joy-Hulga protests so strongly (three times declaring the boy to be a “Christian”, “a fine Christian,” “a perfect Christian”) when he doesn’t act accordingly reveals another humorous layer of irony. Leave it to the atheist to protest the loudest.

In some senses, it seems this story is more pointedly directed to the reader, and challenges hypocrisy in its “Christian” and “non-Christian” forms alike. However, the fact that the boy’s name is “Pointer,” and he points her to the truth, in a manner of speaking, may lend itself to your question of her Joy-Hulga being pointed to grace nonetheless. I suspect “Hopewell” and “Freeman” are also ironical names.