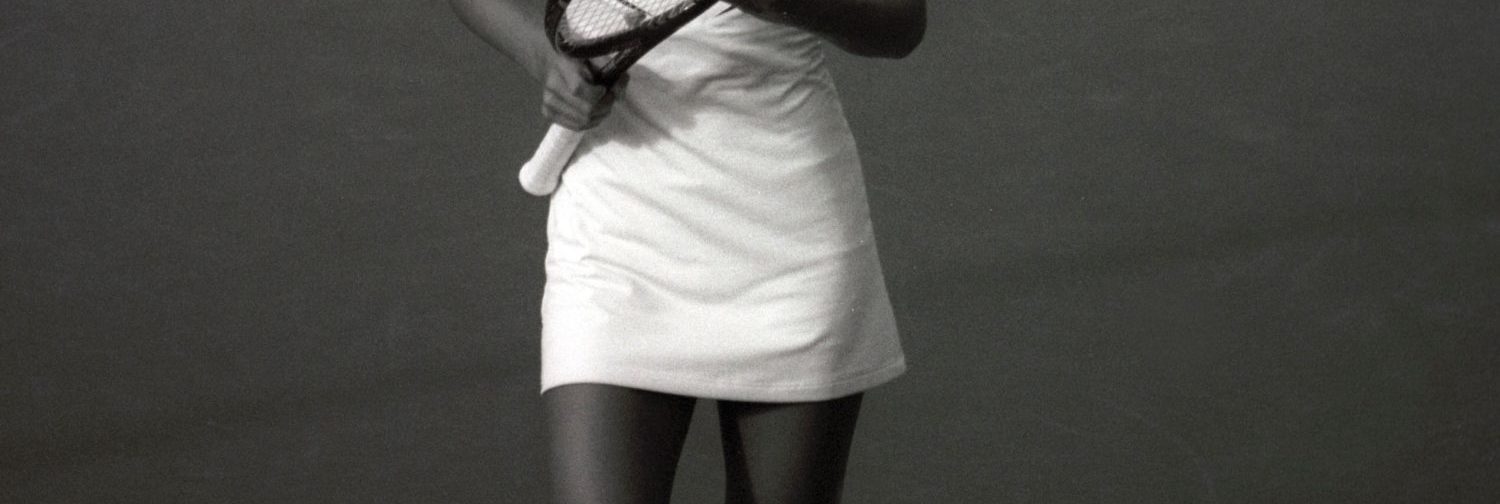

Years ago, my wife Lou Alice took up tennis. She played two or three times a week, went to the clinics, jumped in on the Saturday round-robins. By any reasonable definition, she was a tennis player. But she was reluctant to buy a tennis skirt. It too much like a declaration. More than that, it seemed presumptuous to her. There was always that chance that somebody might say, “Why are you wearing a tennis skirt? You’re not an expert tennis player.”

Eventually I just went up to the sporting goods store, bought a tennis skirt, and brought it home to my wife. Because if you play tennis, you’re a tennis player. You can have a skirt.

As it turned out, putting on the tennis skirt made a big difference for Lou Alice. She felt she had permission to call herself a tennis player, which gave her reason to try a little harder. She joined a league, had a few great summers, and brought considerable glory to the Rogers household with her on-court triumphs in the #6 slot of the Wildwood Tennis Club (Go Gators!).

I understood my wife’s struggle to claim the tennis skirt because I was fresh off my own struggle to claim the name “writer.” It seemed presumptuous. At what point, I was always asking, has one earned the right to declare oneself a writer? When one has a finished manuscript? When one has a literary agent? A book contract? A published book? But really, is one published book even enough? That only means you have written, not that you’re still a writer.

There is only one useful definition of the word writer: a writer is somebody who writes. The title is no more exalted than that. If you’re willing to do the work, you’ve earned the right to call yourself a writer. And calling yourself a writer will give you a little more courage to do the work. So go ahead: claim the title. Put on the tennis skirt.

Deborah Mackall

Exactly. This is my recent conclusion. Thank you for the illustration and confirmation.

Lisa McLean

Thank you *sniff*