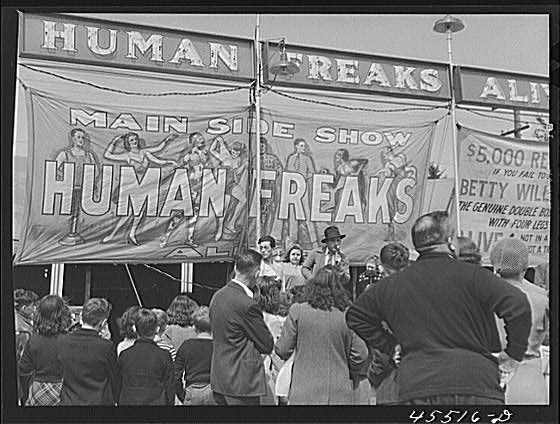

For those who view Flannery O’Connor’s fiction as a freak show, “A Temple of the Holy Ghost” would appear to be Exhibit A. Its most memorable scene describes a hermaphrodite in an actual carnival freak show. But O’Connor doesn’t offer up the hermaphrodite simply as an object of curiosity for gawkers and voyeurs. She doesn’t, in other words, offer up this freak in the spirit of the freak show. The hermaphrodite, to my way of thinking, is surprisingly human, a figure of pathos and even a strange dignity, calling the audience to a civility and charity that one wouldn’t necessarily expect from freak show attendees:

“This is the way [God] wanted me to be, and I ain’t disputing His way. I’m showing you because I got to make the best of it. I expect you to act like ladies and gentlemen. I never done it to myself nor had a thing to do with it but I’m making the best of it. I don’t dispute hit.”

I realize that my impression of the hermaphrodite’s dignity is subjective and that another reader might interpret his/her speech entirely differently. A better clue to the meaning of the hermaphrodite comes from the Tantum ergo, the Latin hymn sung by the Catholic schoolgirls on the porch and sung again during the benediction at the convent. The hymn was written by Thomas Aquinas, whom O’Connor read every night before bed. Here is a translation of the first stanza:

Down in adoration falling,

Lo! the sacred Host we hail,

Lo! o’er ancient forms departing

Newer rites of grace prevail;

Faith for all defects supplying

Where the feeble senses fail.

The hermaphrodite, like the rest of the freaks in O’Connor’s fiction, stands for all of us, broken and needing the grace that supplies our defects. The people who go to the freak show expecting to see a sub-human creature are instead challenged to be more humane, more charitable.

O’Connor once helped some nurse-nuns in an Atlanta with a book called A Memoir of Mary Ann. Mary Ann was a little girl in their hospital whose face was terribly deformed by cancer, but who shone nevertheless with a loveliness that made an indelible impression on everyone who met her. O’Connor wrote the introduction to the book, and in it she provides perhaps the best explanation of what the grotesquerie in her fiction means. I expect to write more about “An Introduction to A Memoir to Mary Ann” in a later post, but for now here is a quotation from the piece that is relevant to the hermaphrodite in “A Temple of the Holy Ghost”:

This action by which charity grows invisibly among us, entwining the living and the dead, is called by the Church the Communion of Saints. It is a communion created upon human imperfection, created from what we make of our grotesque state.

That call to charity is one important role that the hermaphrodite plays in “A Temple of the Holy Ghost”; the twelve-year-old at the center of the story is deeply uncharitable from our first sight of her. She is also beset by an unearned and premature sense of her own superiority. It is the story of the hermaphrodite that brings her face-to-face with the truth that she is living in the midst of mysteries that she cannot fathom. The story of the hermaphrodite is to her “the answer to a riddle that was more puzzling than the riddle itself.” That, perhaps, is the hermaphrodite’s most important role in the story. When the girl finally understands how little she understands about the world she lives in, she is a step closer to receiving the grace that can make up for her shortcomings.

To return to the Tantum ergo, the hermaphrodite’s story is where “the feeble senses fail” for our protagonist. The Eucharist bridges the gap that her human wits cannot cross. Where the girl’s judgmental self-satisfaction had always held sway, “newer rites of grace prevail.” That great blood-soaked elevated Host of the sun makes a red dirt road across the heavens, inviting her to something new.

Chris

I was most struck by this moment in the story: “When the priest raised the monstrance with the Host shining ivory-colored in the center of it, she was thinking of the tent at the fair that had the freak in it. The freak was saying, ‘I don’t dispute hit. This is the way He wanted me to be.'” It seems that O’Connor is making a point about who the body of Christ is (Host = body of Christ = His people). That Jesus came to redeem freaks, and this is what we all our in our own ways.

Loren Warnemuende

This connection into the child’s mind struck me, too. I couldn’t tell if her focus on it meant she had come to a point of excusing her own behavior, “It’s just the way God made me,” because just previously she was asking God to forgive her, or if there was something more. I think you’ve spotted the “more”. Jesus redeemed freaks, and he can redeem her, too.

Jonathan Rogers

I think that’s right; if “The River” is about baptism, this story is about the Eucharist. The girl comes to the end of herself–like the hermaphrodite, she is aware of her own limitations–and the Eucharist carries her the rest of the way.

Philip Wade

Do you think she was connecting the fair with the church in her description: “tents raised in a kind of gold sawdust light and the diamond ring of the ferris wheel” and the chapel “was light green and gold, a series of springing arches”? I wondered if she meant the fair to mock the church in this way.

Also, I love that the happy nun swooped down on the child as she left. That’s hilarious.

Chris

I think, like the host and the hermaphrodite, O’Connor is trying to unite the sacred and the seemingly profane in a way that makes a point about who the citizens of the Kingdom are.

Amy L

I loved that moment with the nun at the end, too. I felt like the nun saw that they shared a mischievous streak, and that hug in itself was an extension of grace to the girl.

April Pickle

Thank you much for the translation. Wonderful!I think the most delightful character in this story is the cook. She has only two lines but they are thoughtful, hilarious, and I think also kind. The “God could strike you” phrase gets repeated by the hermaphrodite and again when the girl is lying in bed, processing the weekend.

Loren Warnemuende

Thank you for giving the Tantum ergo translation. I was dredging up some rusty Latin to try to understand it, but with little success. I knew it couldn’t be there for no purpose and this illuminates that purpose.

Jonathan Rogers

I should probably point out that the translation I provided is not a word-for-word translation. It is, however, a translation that is at least 100 years old, and FO would have probably been familiar with it.

Chris

I found it easily enough on Wikipedia.

Anonymous

Maybe stating the obvious, but I was quickly reminded of Jesus’ parable from Luke 18:9-14 of the Pharisee and the tax collector going up to the temple to pray. While I don’t know if FO’s main point was the same as the one Jesus was making, I can’t help but think it crossed FO’s mind. If the parable was more central, then the child ends up fairing better than the Pharisee. On further thought, the parable begins: “He also told this parable to some who trusted in themselves that they were righteous, and treated others with contempt.” Perhaps the Pharisees end up being the preachers who complained and had the freak show shutdown. (I haven’t read “The End of the Carnival” post yet).