My friend April Pickle encouraged me to write an issue of The Habit in which I pick a couple of sentences I like and tell what I like about them. This shall be that issue. And the sentences I shall write about come from Christian Wiman’s memoir, My Bright Abyss:

They do not happen now, the sandstorms of my childhood, when the western distance ochred and the square emptied, and long before the big wind hit, you could taste the dust on your tongue, could feel the earth under you–and even something in you–seem to loosen slightly. Soon tumbleweeds began to skip and nimble by, a dust devil flickered firelessly in the vacant lot across the street from our house, and birds began rocketing past with their wings shut as if they’d been flung.

I have never experienced a sandstorm. Dust devils never flicker firelessly in my leafy neighborhood here in Nashville, Tennessee. So, to use a phrase I used a couple of weeks ago, these evocative sentences do something for me that I can’t do for myself. They invite me into a scene that I don’t otherwise have access to.

The first thing I’d like you to notice about these sentences is that their great descriptive power comes from the nouns and verbs (and mostly the verbs), not from the adjectives and adverbs. Between them, the two sentences contain 86 words; only three of those words are adjectives: western, vacant, and big. There are a couple of -ly adverbs (slightly and firelessly), and five other adverbs (now, even, soon, by, past).

I realize that adjectives and adverbs exist for the express purpose of describing, so it seems counterintuitive for me to say, as I often do, that nouns and verbs should carry the freight in your descriptive prose. But these sentences from Wiman demonstrate exactly what I’m talking about. These few adjectives and adverbs are very workmanlike, providing specificity but very little flash. (The possible exception is the adverb firelessly, which is pretty evocative, as well as alliterative, in that image of the dust devil flickering firelessly.)

But those nouns and verbs! The sky ochres, the square empties, the big wind hits (or, rather, doesn’t hit yet), you taste the dust, the earth (and something in you) loosens, the tumbleweeds skip and nimble, a dust devil flickers, and birds rocket past as if flung.

Those made-up verbs (or perhaps I should say those verbified adjectives) to ochre and to nimble are remarkable and much more evocative as verbs than they have ever been as adjectives. I realize that this verbification of adjectives is a bit of a cheat and could get old quickly, but used sparingly, it could be a nice trick to have in your back pocket.

I always encourage writers to appeal to as many of the five senses as possible (and reasonable) when inviting a reader into a scene. Here Wiman gives the reader quite a lot of things to look at (and those things are all moving, which is a sensory bonus). He also appeals to the sense of taste (as well as texture, which is to say, the sense of touch) with the dust on the tongue. In the next few sentences, which I am not reproducing here, he doubles down on the sense of touch and introduces the sense of hearing. That’s four out of the five senses.

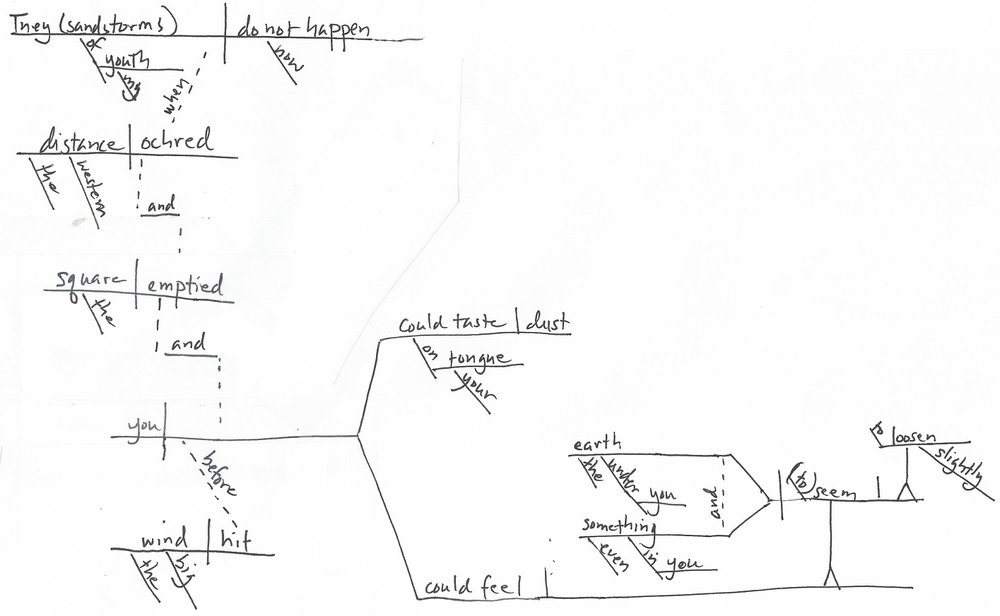

Let us now turn to sentence structure. The grammar in these two sentences is exceedingly complex. Here is my best attempt at a diagram for that first sentence:

That sentence is forty-nine words long. Its main clause includes an appositive, and its subordinate clause is actually a compound of three clauses, the third of which contains its own subordinate clause, a compound verb, and an infinitive phrase with a compound subject. Oh, and that infinitive phrase has another infinitive phrase for its direct object.

And yet when you read this sentence, you don’t have any trouble understanding it. The sentence pulls you in and pulls you along; it only seems difficult when you try to analyze it.

How is it possible that a 49-word sentence doesn’t seem wordy? What we call “wordiness” doesn’t actually depend on word-count. I can show you ten- and twelve-word sentences that are much wordier than this 49-word specimen. A wordy sentence is a sentence in which the words get in the way of clear thought.

I should probably devote a whole letter to this idea, but for now let me say that this long, complex sentence is understandable in large part because as your eye scans from left to right, the meaning unfolds in a rightward direction. The main idea is established in the first clause–They do not happen now. Then the appositive clarifies what we’re talking about–the sandstorms of my youth. And every clause and phrase that follows gives you more information about those old sandstorms in a mostly orderly manner, until the last few words of the sentence.

Have another look at that sentence diagram above. Notice how the straightforward clauses make an orderly march down the page until that last one, when things start to sprawl horizontally. That clause before the big wind hitis the first “left-branching” element in the whole sentence. That is to say, this is the first time in the sentence when a modifying phrase appears before (to the left of) the idea it modifies. And then things get branchy: the verb branches into a compound verb could taste and could feel, and then within the second half of the compound verb, the direct object branches with a compound subject for the infinitive (to) seem. To use the technical sentence-diagramming terminology, we have a rocket ship inside a rocket ship and a stand on top of a stand.

In other words, just before the big wind hits, just as the earth under you and even something in you starts to loosen, the grammar loosens too. I don’t know whether Christian Wiman did that on purpose or by instinct. He is a poet, and I don’t claim to understand how poets’ minds work. But either way, this is brilliant stuff.

If you’re still with me, let’s talk about conjunctions for just a minute. Conjunctions, as you probably know, join elements within a sentence. There are seven coordinating conjunctions–and, or, but, for, so, yet, nor. You should memorize them. There are more subordinating conjunctions than you could possibly memorize (more than fifty, less than a hundred, if I’m not mistaken). A random sampling of subordinating clauses includes because, in spite of, when, where, unless, until, if, though, if only, why, since.

As you can see, conjunctions not only connect elements; they also signal the relationships between those elements. I like my dog, but she smells is a very different sentence from I like my dog because she smells.

Of all the conjunctions, the most neutral is “and.” “And” makes no real claims beyond the fact that two things happened or two things exist. The sentence I like my dog and she smells doesn’t explain anything about the relationship between my affection for my dog and her smelliness.

When I teach academic writing, I tell my students not to waste their conjunctions. Academic writing is all about articulating the relationships between ideas. One thing happened because of another thing. Or a thing happened in spite of a another thing. One thing is true if another thing is true. Or one thing is true since another thing is true. Because and doesn’t address those kinds of relationships, in academic writing and is often a waste of a conjunction.

But look at Christian Wiman’s conjunctions. In the two sentences I quoted above, you will find five instances of the conjunction and. (You will also find the subordinating conjunctions when, before, and as if, but I have tried your patience already, so I’m not getting into that.)

Why so many ands, and why are these not wasted conjunctions? These two sentences are all about sensory experience. Sensory experience comes to us without the kind of explanatory, interpretive information that subordinating conjunctions provide. Tumbleweeds skip and nimble by, and dust devils swirl, and birds rocket past. That’s just data that comes in through your eyeballs. Your brain then goes to work on that data and interprets it.

The five ands in these two sentences are a clue to how the sentences work: Wiman is inviting us into a scene, showing us what we would see (and taste) if we were in that West Texas town just before a sandstorm blew in. Then, rather than explaining or interpreting, he trusts us to interpret that data for ourselves, just as we do every minute of every day in the world God made.