The nominative absolute is one of those grammatical structures that you don’t hear a lot about, though you see it and probably use it all the time. I was in my forties before I knew what a nominative absolute was, and I had a Ph.D. in English, so if the nominative absolute is new to you, no worries.

We’ll start with examples, then go to definitions. Each of the following sentences begins with a nominative absolute (in bold):

- All things considered, that wasn’t such a bad riot.

- All things being equal, I like tea better than spoiled milk.

- The foghorn sounding in the distance, we approached the harbor.

As you can see from the above examples, a nominative absolute is made up of a noun with its modifiers. Those modifiers typically (though not always) include a participle or participial phrase. That participle/participial phrase may be either past or present. In things considered, the noun things is modified by the past participle considered. In things being equal, the phrase being equal is a present participial phrase.

A nominative absolute most often sits at the beginning of a sentence, but it can easily be moved to the end, as in

That wasn’t such a bad riot, all things considered.

But not every noun modified by a participle constitutes a nominative absolute. Consider these sentences, which I will call Sentences 4 and 5:

4. My dog, having chewed up my retainer again, looked guilty.

5. My dog having chewed up my retainer again, I made another trip to the orthodontist.

In each of these sentences, the first seven words in bold are the same. But only one of those bold phrases is a nominative absolute. When you discern the difference between these two sentences, you will understand what a nominative absolute is.

The nominative absolute, by definition, has no grammatical connection to any part of the sentence where it lives. The noun at the root of the nominative absolute is not a subject, a direct object, an indirect object, an object of a preposition, or a predicate nominative. The phrase as a whole isn’t adjectival modifying a noun or adverbial modifying a verb, adjective, or adverb. The word absolute is from the Latin, absolutus, which means “set free.” Nominative is another word for noun, so a nominative absolute is a noun phrase that has been set free from its sentence.

So let’s look again at the bold phrases in sentences 4 and 5. Pay particular attention to that noun dog. In one sentence dog is a grammatical free agent, and in one dog serves a crucial grammatical role. Do you see the difference? I’ll wait…

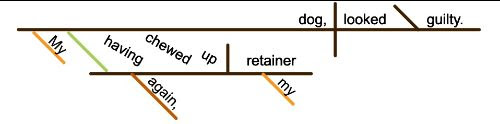

In Sentence 4, dog is the subject of the verb looked. Here’s the diagram, if it helps (and if I diagrammed it correctly!):

There’s dog on the main line of that sentence diagram. It can’t be a nominative absolute. And the participial phrase having chewed up my retainer again attaches to the main line because it modifies the grammatical subject.

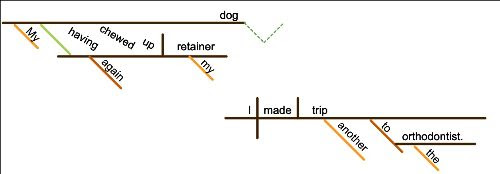

Now look at Sentence 5. What’s the subject-verb nexus? I made. Grammatically speaking, the dog and the retainer are completely independent of the main clause. Here’s the diagram:

As you can see, the nominative absolute doesn’t touch the diagram of the main sentence. Where would it go if it did? The noun dog has no relationship to the main verb, either as a subject, object, or complement. It doesn’t modify the subject or the verb or the direct object, or any of the modifiers branching off the main line.

One quick note before moving on: A nominative absolute can be as long as you want. To wit:

My dog having chewed up my retainer in the dark of night while I slept the sleep of the blessed, completely unaware of the nefarious deeds being committed in the next room, I made another trip to the orthodontist.

I won’t diagram that one, but the main line is the same as in the diagram above—I made another trip to the orthodontist—while the nominative absolute balloons. It’s not a great sentence; it makes the reader wait way too long for the subject-verb nexus. But it’s not incorrect grammatically.

So if the nominative absolute has no grammatical connection to the main sentence, why is it there at all? What sort of connection does it have, if not a grammatical connection? It has a logical connection. It provides explanatory information that adds meaning to the main sentence. It’s not technically adverbial, because you can’t identify a verb, adjective, or adverb that it modifies. But it feels adverbial, in that it comments on the whole action of the sentence.

Here’s an example of a nominative absolute that doesn’t have a logical connection to the main clause:

My grandmother having been born in 1918, I picked up some grocery-store sushi.

In such a sentence, the nominative absolute has no reason to exist.

I warn writers against over-using the nominative absolute. It’s a complex structure, so it sounds very sophisticated. But nominative absolutes tend to become a sort of verbal habit, and that gets wearying for the reader, who doesn’t have as much patience for writerly sophistication as the writer does. By definition, a nominative absolute introduces a disconnect into your sentence. You’re shooting for connection, so always ask yourself if it’s really necessary.

It feels good to be sophisticated. I get that. If you want to seem more sophisticated, consider getting yourself a black turtleneck and a beret rather than subjecting your reader to too nominative absolutes or similarly sophisticated grammatical structures.