I’ve been reading two excellent books about writing. One is George Saunders’s A Swim in a Pond in the Rain: In Which Four Russians Give a Master Class on Writing, Reading, and Life. The book consists of seven short stories by Russian writers, each followed by a detailed analysis by Saunders. It’s shaping up to be the best book about fiction-writing I’ve ever read. On Thursday I’ll be doing a webinar-workshop with The Habit Membership in which we’ll work through an especially interesting exercise from that book. I’m sure I’ll have more to say about A Swim in a Pond in the Rain in a later issue of The Habit Weekly.

The second book is Essays One, a collection of essays by Lydia Davis. It’s not, properly speaking, a book about writing, but a good many of the essays in the collection are about writing. One of the best is “Thirty Recommendations for Good Writing Habits” (you can read an abridged version—involving ten of the thirty recommendations—here).

A lot of Lydia Davis’s recommendations simply come down to paying attention to the world around you, and then making a record of what you have seen. Here’s her first recommendation:

Take notes regularly. This will sharpen both your powers of observation and your expressive ability. A productive feedback loop is established: through the habit of taking notes, you will inevitably come to observe more; observing more, you will have more to note down.

This is an excellent reminder for me. I don’t do a great job of writing things down, or of keeping up with them when I do. (I will say, however, that my bad habit of writing things on scraps of paper, then losing the scraps of paper hasn’t been all bad. More than once, the right scrap has reappeared at just the right time, and the scrappiness often means that the newly-found note is completely out of context—which makes it amenable to a new context.)

It’s important, I think, for a writer’s notebook to be a notice-book—here are some things I’ve noticed—and not just a record of the writer’s interior life. Your feelings are an appropriate subject for your notebook, but I hope they won’t be the book’s main subject. There’s too much to see in the world. “The writer should never be ashamed of staring,” wrote Flannery O’Connor. “There is nothing that doesn’t require his attention.”

If you are a young writer, it is especially important that you look outward and not just inward. I have a journal I kept when I was nineteen or twenty. It’s page after page about what was going on inside me. You wouldn’t believe how boring my big ideas were. What I really want to know is who I was hanging out with back then, where we went, the things I ate, some of the things I saw.

In her list of what to notice in your notebook, Davis writes, “Observe your feelings (but not at tiresome length.)” Then, a couple of pages later, she writes, “Observe the weather, and be specific.” There’s an insight for you: Your feelings are worth writing down. So is the weather.

Here’s an example from Davis’s notebook of what it means to observe the weather, and be specific:

High wind yesterday blew women’s long hair, women’s long skirts, crowns of trees, at dinner outdoors, napkins off laps, lettuce off plates, flakes of pastry off plates onto sidewalk.

She continues,

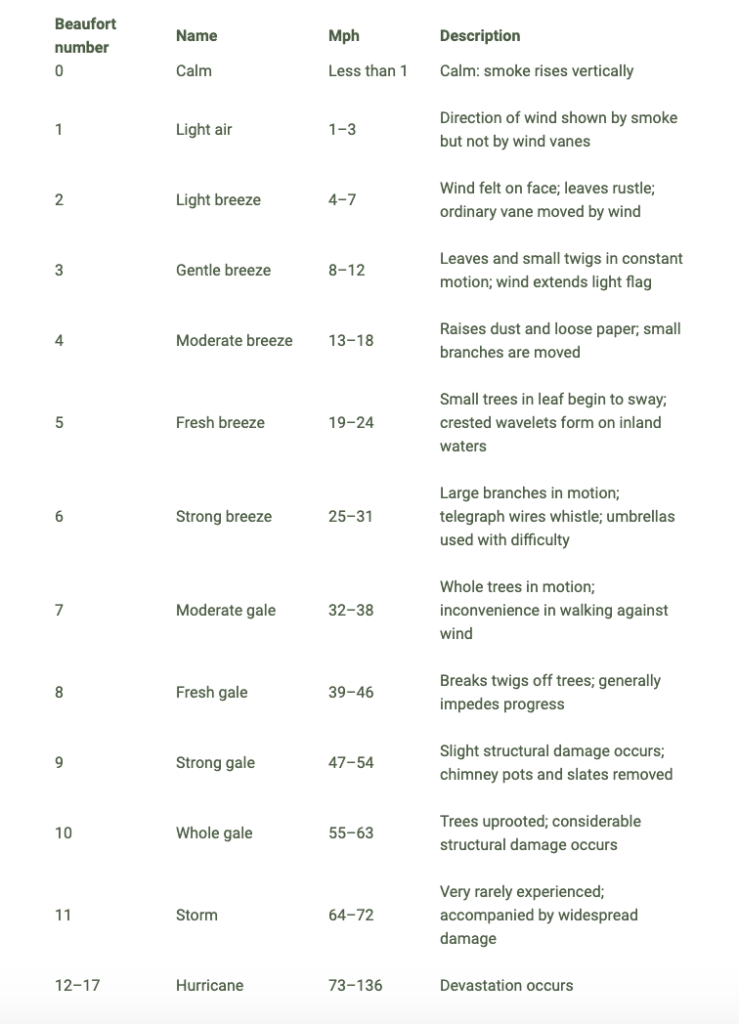

Apropos of weather and precision, here is the 1970 Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary chart of the Beaufort scale—a scale in which the force of the wind is indicated by numbers from 0 to 12. This source is “just” a dictionary, but the images are vivid because of their specificity and the good clear writing in the dictionary, and because the increasing strength of the wind on the scale becomes, despite the dry, factual account, dramatic.

Those descriptions in the fourth column make me so happy. Columns One and Three are just numbers—precise in the way numbers are precise, but pretty bloodless. The names in Column Two are really just abstractions. But when you say that “light air” blows smoke but doesn’t move a wind vane—now we’re getting somewhere. Here is where it becomes apparent that the observational skills of a scientist have a lot of overlap with the observational skills of a good writer.

Which brings me to the other recommendation from Davis’s essay that I’d like to bring to your attention: “Always work (note, write) from your own interest, never from what you think you should be noting or writing. Trust your own interest…Let your interest, and particularly what you want to write about, be tested by time, not by other people—either real other people or imagined other people.”

Yes.

I’m not sure you ever need to ask another person, “What should I write about?” Your interest is perhaps the most important way you can identify the patch of ground that is yours to tend.

I would also add, however, that you need to be open to having your interests changed and expanded. When I woke up this morning, I didn’t know I was interested in the Beaufort Wind Force Scale. But as it turns out, I am.