A couple of weeks ago, in a letter called “Smoking Gun,” I wrote about the second principal part of English verbs. I indicated that, should there be sufficient demand, I might be willing to write about the other three principal parts. Well, dear readers, eight of you asked for a letter covering all four principal parts of English verbs. I’m going to assume that those eight readers speak for the other 6228 of you, especially since nobody wrote to ask me not to write more about the principal parts. Which is to say, thank you for the overwhelming demand. I have heard you.

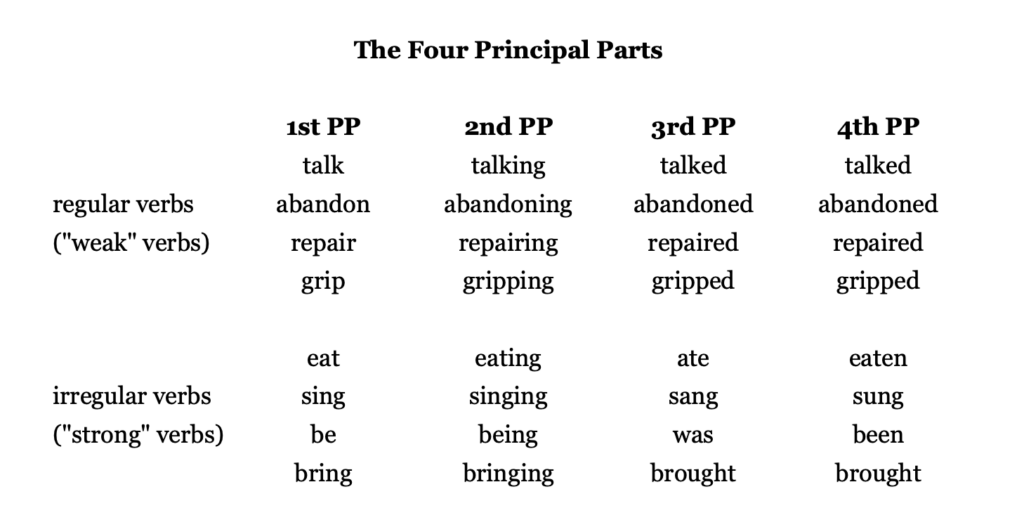

Every verb has four “principal parts.” Here is a chart showing the four principal parts for four “regular verbs” and four “irregular” (or “strong”) verbs. You can refer to it as we walk through the four parts below:

The First Principal Part

The first principal part of a verb is its “infinitive” form. Stick a “to” in front of the first principal part, and you you have the verb’s infinitive: to talk, to abandon, to eat, to sing, to be. The first principal part is also the simple present-tense form of the verb for all “persons” other than third-person singular: I repair, you repair, we repair, they repair. For third-person singular simple present tense, add an -s to the first principal part: he/she/it repairs. The only exception, as far as I know, is the to be verb, which forms the simple present in a way that is calculated to frustrate anyone learning English as a second language: I am, you are, he/she/it is, we are, they are.

The Second Principal Part

The second principal part is the -ing form of the verb. As I mentioned two weeks ago, this principal part is used to form the various progressive tenses (I was singing, I am singing, I will be singing). The second principal part also forms the present participle (talking parrots) and the gerund (Eating is my favorite pastime). If you need a refresher, I refer you to my earlier letter about the second principal part.

The Third Principal Part

The third principal part has only one job: it forms the simple past tense of the verb. I talked. You talked. He/she/it talked. We sang. You sang. They sang. It is here in the third principal part that we begin to see the difference between regular and irregular verbs.

For a regular verb, you form the past tense by adding -d, -ed, or -t. Talk becomes talked, televise becomes televised. For irregular verbs, you form the past tense by changing the vowel, and possibly more than that. Sing becomes sang, bring becomes brought, go becomes went, is becomes was.

The vowel-changing in irregular verbs goes back to Anglo-Saxon (Old English), which formed tenses by changing vowels rather than changing endings. It is my understanding that all irregular verbs in English come from Anglo-Saxon. The formation of the past tense by adding -d, -ed, or -t came along later. Any verb that entered the language via Norman French or Latin or Greek will be a regular verb. The Latinate illuminate/illuminated is regular. The Anglo-Saxon light/lit is irregular. Same with the Latinate ingest/ingested and the Anglo-Saxon eat/ate. Impel/impelled vs. drive/drove. Ascend/ascended vs. rise/rose. You can do this all day long. Also, new verbs are always regular. The past tense of Google is Googled. The past tense of email is emailed.

But not all English verbs of Anglo-Saxon origin are irregular. Many (most?) surviving Anglo-Saxon verbs gave up and complied with the new regime of past-tense endings. Help is a regular verb: its third principal part is helped. But before 1300 or so, the past tense of help was holp. (When my father was growing up, he knew old-timers who used holped as the past tense of help. Maybe that was some kind of late survival?) All Anglo-Saxon verbs started out “irregular.” The ones that are still irregular are sometimes called “strong verbs,” because they resisted the grammatical changes of Middle and Modern English. Regular verbs, by contrast, are sometimes called “weak verbs.”

The Fourth Principal Part

Here’s how I remember the fourth principal part: it’s the form of a verb that you would use after the auxiliary verb have or has. I have talked. You have gripped. She has eaten. They have sung.

As you can see from the chart above, for regular verbs the third principal part and fourth principal part look identical: I talked. I have talked. You repaired. You have repaired. For irregular verbs, the third and fourth parts may be identical—I brought, I have brought—or they may be different—I ate, I have eaten.

Mixing up the third and fourth principal parts is one of the most common grammar mistakes. If you are writing dialogue and want to signal that one of your characters speaks non-standard English, just a sprinkling of confused third and fourth principal parts can do wonders. “She has ate already,” for instance, or “She begun eating before I did.”

That’s that the fourth principal part looks like. But what does it do? The fourth principal part has three main uses:

The Perfect Verb Tenses

Combined with an auxiliary verb (or two), the fourth principal part forms the perfect verb tenses. Whereas the simple past tense (third principal part) signals that an action happened in the past, the perfect verb tenses signal that an action was/is/will be complete at a point in time signified by the auxiliary verb(s):

- I have eaten. (present perfect)

- I had eaten. (past perfect)

- I will have eaten. (future perfect)

The Passive Voice

Combined with a to be verb, the fourth principal part forms the passive voice. In short, the passive voice flips a sentence around such that the recipient of an action becomes the grammatical subject of the sentence:

- A lamp was broken.

- Consuela was chased by a raccoon.

- Barbie was given flowers by Ken.

You can learn quite a bit more about the passive voice in this old issue of The Habit Weekly. (There are also a couple of videos if you learn better that way.)

The Past Participle (Passive Participle?)

As I discussed in the “Smoking Gun” letter, a participle is a verb form used to modify a noun. The second principal part forms the present participle (flying pig, dancing bear). The fourth principal part forms the past participle (mashed potatoes, spoken English).

Nobody asked me, but if they had, I would have suggested that the past participle be called the passive participle. And the present participle I would have called the active participle. It’s true that spoken and mashed are perfect verb forms, which are past-y, and flying and dancing are progressive verb forms, which are present-y. But the more relevant fact, I think, is that in a “present” participle, the noun is doing something—the pig is flying, the bear is dancing—whereas in a “past” participle, the noun has been the recipient of an action. The potatoes have gotten mashed. The English has been spoken.

Furthermore, consider the fact that an intransitive verb (a verb that can’t take a direct object) can’t be used in a “past” participle, just as it can’t it be used in a passive construction. Because a passive construction turns an object into a subject, a verb with no object can’t be turned passive. Slept is a good example of an intransitive verb. I can only say “I slept,” not “I slept a nap.” Therefore I can’t make a passive sentence such as “The nap was slept by me.” For the exact same reason I can’t use slept as a past participle in a phrase like “the slept nap.” I can, however, make the present participle “a sleeping dog.” One more reason to call these grammatical forms active participles and passive participles.

People don’t formulate new grammar theories all that often, but I’ve proposed two in two weeks: the “Certain-Present-Participles-Are-Actually-Gerund-As-Objects-of-Implied-Prepositional-Phrases Theory” from two weeks ago, and today’s “Past-Participles-Are-Actually-Passive-Participles” Theory. It’s an exciting time to be a Habit Weekly reader.

Johnsina Molsom

Thanks 👍